Virtual Clouds, Does Digital Privacy End With Death?

The Corona Outbreak Has allowed Us To Think More Seriously About Death. Now That Our Lives Are Increasingly Digital, We Are Experiencing A New Style Of Death In This Digital World.

An experience with unique challenges. With their death, humans leave a lot of information online.

The volume of digital information is growing rapidly, and now a significant portion of this stored information belongs to millions of souls online! According to experts, the epidemic of the new corona has increased the volume of this digital heritage, and now we are faced with a large number of abandoned profiles whose owners have died.

The question now is how should we manage the digital heritage and what is the place of privacy and ethics? Scholars have called death in the modern world a hidden death. This naming is because, in modern times, most people spend the last moments of their lives in medical centers and few people except the medical staff see their deaths.

Some experts now believe that with the pervasiveness of digital technology, we are in the throes of a hidden death.

The digital legacy and profiles that deceased people leave on social media have once again made death public, this time in cyberspace.

If a user dies, their audience will notice the loss. The deceased are now permanently available through cell phones, social networks, images, and videos of them on physical storage media or the cloud. This encounter with the death of our loved ones may be a unique experience.

The online data we leave behind after death is called digital heritage. Of course, this is a broader concept and is not limited to online data or what is left of us on virtual clouds, but also to everything we store on storage media, mobile phones, and other personal devices.

The existence of this digital heritage has also boosted businesses operating under the umbrella of “digital life after death”.

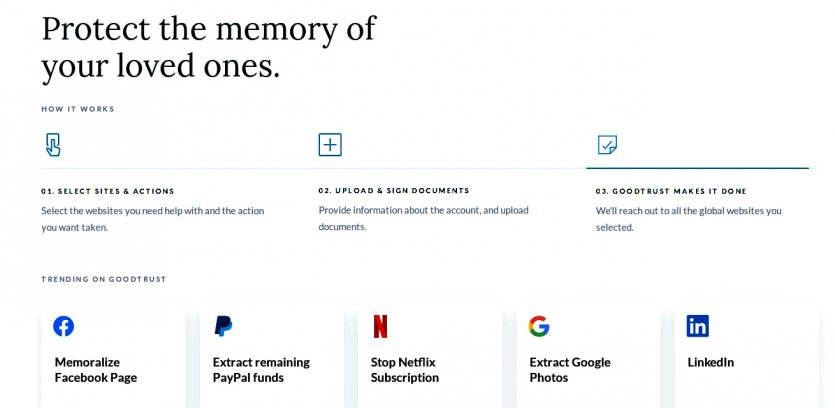

Managing the deceased’s digital information, holding an online memorial service, digitally simulating the deceased, and sending a message from the deceased to his or her relatives are some of the services based on users’ digital heritage (Figure 1).

But what matters most, and we will focus on here, are the challenges that death entails; These challenges include issues of privacy and digital life after death.

Digital Death

Carl Öhman, a researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute, predicts that in less than 50 years, the death toll on Facebook will be higher than the number of the living, and could rise to about one billion in the next three decades.

It is difficult to estimate how much online content will be relevant to these accounts, but experts believe that this is a morally sensitive issue and that this new style of death requires new ethical considerations.

There is no standard way to deal with digital heritage and we need to set such standards. Studies have shown that relatives of the deceased take different approaches to their digital heritage. For example, the mother of a deceased child may decide to delete any trace of her child on the Internet.

Figure 1 – With the prevalence of coronation, remote burial ceremonies have become more common and companies offer such services.

Privacy of the deceased

It is almost certain that there is no law to protect the privacy of the deceased. For example, the EU General Data Protection Regulations, or GDPR for short, which is one of the most powerful frameworks for information privacy, clearly states that these rules only cover the living world!

Thus, the deceased are in no way under the protection of the EU Information Protection Act. Some EU members have considered safeguards independently, one of the best examples of which is Denmark.

But the general rule in the world is that with the death of a user, all privacy rights are taken away from him and companies can do whatever they want with his data.

According to Jed Brubaker, there is no doubt that the commercial development of Covid 19 has significantly contributed to the growth of digital posthumous digital life management.

He has helped Facebook launch a service that allows the user to choose someone to inherit their account.

Brubaker points out that focus of digital assets is often focused on financial debates, and that assets such as social media or items such as Netflix network subscriptions are neglected.

This is where startups like the Japanese startup Hanamaru Syukatsu or the American company GoodTrust come into play (Figure 2). Such digital heritage management platforms help customers secure their digital assets and properly archive their digital memories.

Founder of GoodTrust, who recently published a book entitled “Digital Heritage: “Take control of your online life after death,” he said, adding that managing online life after death poses challenges to survivors that vary depending on where the deceased lives.

In the United States, for example, when a person dies, a separate court order is required to access each of that person’s online accounts. The issue of accessing the accounts of deceased people in other countries maybe even more complicated.

Because the survivors will go directly to the big tech companies as soon as they change ownership of the deceased’s account or delete the subscription. Brubaker believes that Internet users need more support at the end of their lives.

According to him, Covid has made 19 deaths a part of our lives, and know that our lives have become more digital, technology must come to the rescue.

In the United States, for example, when a person dies, a separate court order is required to access each of that person’s online accounts. The issue of accessing the accounts of deceased people in other countries maybe even more complicated. Because the survivors will go directly to the big tech companies as soon as they change ownership of the deceased’s account or delete the subscription.

Brubaker believes that Internet users need more support at the end of their lives. According to him, Covid has made 19 deaths a part of our lives, and know that our lives have become more digital, technology must come to the rescue.

In the United States, for example, when a person dies, a separate court order is required to access each of that person’s online accounts. The issue of accessing the accounts of deceased people in other countries maybe even more complicated.

Because the survivors will go directly to the big tech companies as soon as they change ownership of the deceased’s account or delete the subscription.

Brubaker believes that Internet users need more support at the end of their lives.

According to him, Covid has made 19 deaths a part of our lives, and know that our lives have become more digital, technology must come to the rescue. Brubaker believes that Internet users need more support at the end of their lives.

According to him, Covid has made 19 deaths a part of our lives, and know that our lives have become more digital, technology must come to the rescue. Brubaker believes that Internet users need more support at the end of their lives.

According to him, Covid has made 19 deaths a part of our lives, and know that our lives have become more digital, technology must come to the rescue.

Figure 2 – GoodTrust is one of the companies offering digital heritage management services. With the help of this company, applicants can manage their digital assets, including social media sharing and even platforms such as Netflix, after their death.

Unjust lawlessness

Faheem Hussain, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona, is concerned about how residents of the less developed parts of the world are affected by the challenges posed by digital life after death.

The large number of Facebook users who have died in recent years have come from less developed countries, especially India and Indonesia. Examining Facebook’s post-mortem digital life policies, he found that residents of less developed countries were more vulnerable to digital assets.

In many countries, there are no laws or mechanisms to protect people after their death. We can already see signs of the effects of such legal loopholes.

For example, inactive Internet accounts of deceased people are attacked by hackers, and according to the findings of the cybersecurity company NortonLifeLock, nearly 500 million customers in only ten countries have been victims of cybercrime, and 350 million of these crimes are related to 2019 alone.

In addition, nearly 46 million Internet users were victims of identity theft in 2019.

Ghosts inhabiting cyberspace

Carl Öhman. In the article “Has death taken over Facebook?” It is claimed that mainstream social media has become a digital graveyard. The article claims that by the end of the century, billions of digital legacies may be buried in Facebook, far beyond the population of live Facebook users.

This trend poses new and serious challenges to social media. Although what the dead are currently doing on social networks such as Facebook does not have a significant commercial impact on social media companies, given the mortality rate we see today, this trend is rapidly becoming a major challenge for these companies.

In the next few decades alone, hundreds of millions, or rather billions of dead profiles, will remain on Facebook.

If we want to look at it from the perspective of a company like Facebook, since many business models rely on advertising sales, user data is valuable when it can be used to attract attention and increase clicks.

According to these companies, the accounts of deceased users occupy only the server space and have no economic benefit.

Unless we either re-enter such data into the business cycle or delete it forever.

But from a moral point of view, both of these options will have anomalous effects. Imagine the relatives of the deceased paying to maintain the social network of the deceased. It’s just like buying a tombstone in the real world.

However, this preserves the data of the deceased, and subsequent generations can access this data, which is actually part of that person’s life history, but there is a problem. With such an approach, those who pay can preserve their digital past or that of their relatives. On the other hand, Facebook will delete any accounts that may be worth keeping just because they have no economic benefit.

Questions about the future

Although we are talking about the approach of a company like Facebook to the data leftover from the dead, we can go a step further and ask another question. Who knows if Facebook will exist in the next two decades or not?

What if Facebook goes down and a completely different platform comes into play, and even this question, what if Facebook goes bankrupt or is forced to shut down?

Normally, if this happens, all of the company’s assets will be sold. In this example, assets are the same as user data. Of course, in some cases, some laws provide for a degree of protection.

For example, the EU GDPR states: “You can not sell this data to companies that are not active in that industry and users have the right to discard their data if they wish.” However, this law is not universal and the GDPR does not apply to the dead.

So if Facebook shuts down, all data about users who have died and most likely live users living in areas not covered by the GDPR can be sold to anyone.

Ethics in the virtual cemetery

The outbreak of coronation has forced people to turn to the online world for everyday tasks, even to hold old rituals such as commemorating the dead.

However, many of them do not know what contract they are signing to use these services and are unaware of the fact that their online life will last longer than their real life.

Although digital technology has made life easier, especially in the current context of the Corona outbreak, it has also created problems that play a significant part in privacy.

Large technology companies now have large amounts of user data in the shadow of legal loopholes in most countries.

Companies such as Google, Facebook, and LinkedIn can play a significant role in managing post-mortem user data. Experts believe that digital data forms an important part of people’s identities.